Memory Becomes Movement

Associate professor Kim Jones resurrects forgotten Korean dancer Choi Seung Hee

By Meg Whalen

Photos by Kat Lawrence

When Choi Seung Hee was purged in 1960s North Korea, her legacy, like her life, could have been snuffed out. Widely regarded as Korea’s first modern dancer, Choi had developed an international reputation in the 1930s, touring Europe and the United States. But the turmoil of the next two decades – World War II, the Korean War and the triumph of Communism in China and North Korea – charted a different path for the cosmopolitan choreographer and dancer.

Associate Professor of Dance Kim Jones had never heard of Choi Seung Hee until about 15 years ago, when a friend showed her a short video about Choi. Being both Korean (on her mother’s side) and a modern dancer (she was a Martha Graham Dance Company member), Jones was intrigued.

“Then I didn’t think about her again for 10 years or so.”

Photo by Kat Lawrence

In the ensuing decade, Jones developed a reputation as a researcher and recreator of historical dances. In 2013, she brought to life a lost solo that modern dance pioneer Martha Graham had choreographed in 1935. Pieced together through interviews with former Graham dancers and archival study of photographs, newspaper articles and other materials, the reimagined “Imperial Gesture” garnered attention from the New York Times and, after performances in Charlotte and New York City, was accepted into the Graham Company’s repertory.

Just three years later, Jones was asked to rescue another work from obscurity: “Tracer,” a 1962 work by the famed modern dance choreographer Paul Taylor. That work, also covered in the New York Times, is now performed by the Paul Taylor Dance Company.

It was while she was wrapping up her research on “Tracer” that Jones recalled the film of Choi Seung Hee.

“I was thinking about my own culture and thought, let me investigate her more,” she said.

Famous then Forgotten

Choi Seung Hee was born in Japanese Imperial Korea in 1911 and, as required by the colonial government, adopted a Japanese version of her name, Sai Shōki. When she was 15, she saw the Japanese modern dancer Ishii Baku perform in Seoul and was inspired to become a dancer. After convincing her parents to allow it, she traveled to Tokyo and spent three years studying with Baku before returning to Korea, marrying and beginning her career.

Choi’s brother and husband were both sympathetic to socialist politics, and Choi — like European and American early modern dancers such as Mary Wigman and Martha Graham — was attracted by many of the ideals of socialism, particularly the emphasis on feminism and the dignity of the working class. With works like “A Free Person’s Dance” (1931), Choi began to create a Korean sinmuyong, or “new dance” that challenged Japanese Imperialism and traditional notions of femininity.

“There’s a writing where she says, ‘I dance for freedom,’” Jones said. “And I said, oh my gosh — freedom of her country, freedom as a woman, freedom as a Korean.”

Choi’s talent was prodigious, but political and cultural pressures were great. Turning away from socialist realism, she began to add more traditional Korean dance elements to her choreography and by the late 1930s was touring across the globe. When World War II broke out, the Japanese government sent her to entertain Japanese troops, which, once the war ended and Korea was liberated, prompted criticism from Korean nationalists.

In 1946, Choi’s husband, an active supporter of the Workers’ Party of Korea, went to North Korea, and Choi soon followed. She founded a school, toured China, the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, and began again to create dances with socialist realist themes. But eventually, internal strife within the regime led to a series of purges. Choi’s husband was arrested in 1959 and killed; Choi disappeared in 1967. In 2003, North Korea issued an official statement that she had died in 1969.

Ending up on the wrong side of a geographic and ideological border, Choi became more sullied than celebrated in South Korea and knowledge of her faded.

“It’s such a sad story — a story of war, of assimilation, of erasure,” said Jones.

RIGHTING THE HISTORY

In studios and classrooms in the United States, the known history and techniques of modern dance have been almost exclusively American and European. Research like Jones’s is opening up that tunnel vision.

“What we’re beginning to uncover is that there really were dance modernisms globally,” said Susan Manning, a professor at Northwestern University in Illinois and the author of the forthcoming “Critical Histories of Modern Dance.” “How does this history happen, and we not learn it?”

Photo by YeJin Lee: Dance professor Kim Jones coaching dancer

So Young An for “Dance for Freedom.”

While Manning and other scholars are writing new histories of global modern dance that explore contributions like Choi’s, Jones is bringing that history to the stage in movement that is rooted in the research and resonates with her own dance training, her personal story and the connection she feels to Choi.

“What Kim is doing is very urgent for this moment. She’s not arguing that she’s actually recreating this dance. It’s lost. But how do we reimagine, reperform, reenact, rethink, recover? Kim’s work is making a huge difference in terms of how we understand modern dance.”

– Susan Manning, Bergen Evans Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University

자유 Dance for Freedom

Photo by Botticelli Foto: Kim Jones and musician Vong Pak perform at a festival in Italy

In late 2019, Jones received a Faculty Research Grant to travel to Korea to meet again with Choi’s former dance student, Kim Yeong-Sun, a North Korean refugee in her late 80s. But the pandemic prevented the spring 2020 trip. Fortunately, So Young An, a current member of the Martha Graham Dance Company, was in Korea at the time. Jones was able to connect her to Kim Yeong-Sun, and with the help of Zoom and production manager Hae Jin Han, could join the two dancers as An learned the historical dance movements.

A year later, Jones, An, and Korean musician Vong Pak came together in person in New York City to begin to create a new work: “자유 Dance for Freedom: Re-imagining the Dances of Choi Seung Hee.”

“When I first heard about this project, it was like my destiny,” said Pak. “Choi Seung Hee inspires me as a diasporic artist. She fought for women in society, for freedom of dance movement. That’s why she is great.”

Jones said that the creative process has “truly been an exercise in collaboration,” with Pak, Han, and An all contributing to the work’s development. Jones and Pak gave a preliminary performance at the Danza Arte Pietra in Italy in June 2022. In January 2023, Pak and An gave the definitive premiere of “Dance for Freedom” at UNC Charlotte’s Faculty Dance Concert.

The 17-minute work, which Jones plans to expand to an evening-length program, opens with a video by Han of Korean pots in the rain. As the rain subsides, the sound of a chime in the wind fades into the meditative tone of the jing, or Korean gong, as Pak, seated at the far side of the stage, begins to play.

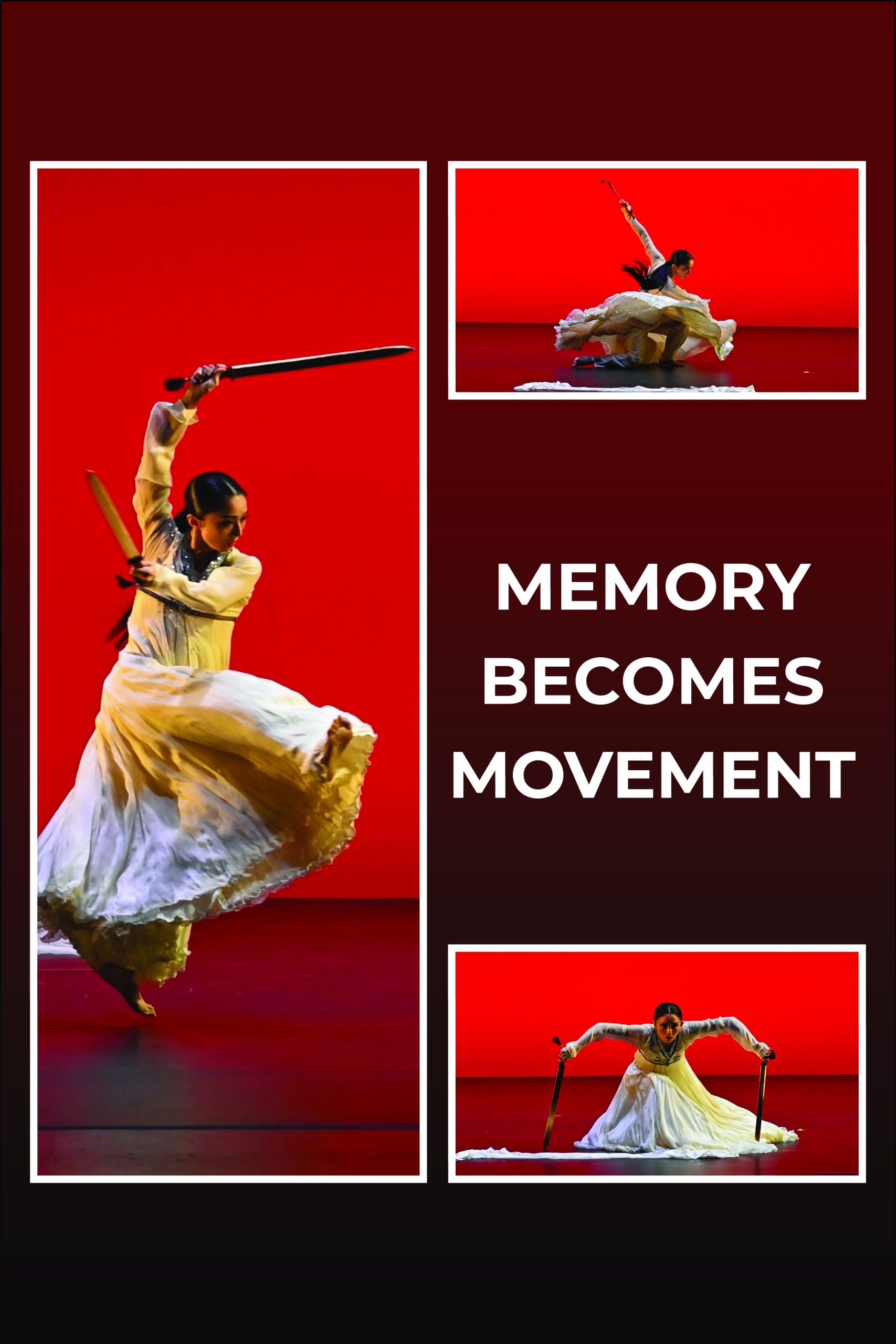

Resplendent in a gown of white Korean silk, So Young An emerges slowly from a long gossamer veil, like a bride. Or maybe a ghost become flesh, turning memory into movement and music.

RELATED STORIES:

Kim Jones awarded New York Public Library Fellowship

Meg Whalen is director of communications for the College of Arts + Architecture.

Associate professor Kim Jones resurrects forgotten Korean dancer Choi Seung Hee

By Meg Whalen

Photos by Kat Lawrence

When Choi Seung Hee was purged in 1960s North Korea, her legacy, like her life, could have been snuffed out. Widely regarded as Korea’s first modern dancer, Choi had developed an international reputation in the 1930s, touring Europe and the United States. But the turmoil of the next two decades – World War II, the Korean War and the triumph of Communism in China and North Korea – charted a different path for the cosmopolitan choreographer and dancer.

Associate Professor of Dance Kim Jones had never heard of Choi Seung Hee until about 15 years ago, when a friend showed her a short video about Choi. Being both Korean (on her mother’s side) and a modern dancer (she was a Martha Graham Dance Company member), Jones was intrigued.

“Then I didn’t think about her again for 10 years or so.”

Photo by Kat Lawrence

In the ensuing decade, Jones developed a reputation as a researcher and recreator of historical dances. In 2013, she brought to life a lost solo that modern dance pioneer Martha Graham had choreographed in 1935. Pieced together through interviews with former Graham dancers and archival study of photographs, newspaper articles and other materials, the reimagined “Imperial Gesture” garnered attention from the New York Times and, after performances in Charlotte and New York City, was accepted into the Graham Company’s repertory.

Just three years later, Jones was asked to rescue another work from obscurity: “Tracer,” a 1962 work by the famed modern dance choreographer Paul Taylor. That work, also covered in the New York Times, is now performed by the Paul Taylor Dance Company.

It was while she was wrapping up her research on “Tracer” that Jones recalled the film of Choi Seung Hee.

“I was thinking about my own culture and thought, let me investigate her more,” she said.

Famous then Forgotten

Choi Seung Hee was born in Japanese Imperial Korea in 1911 and, as required by the colonial government, adopted a Japanese version of her name, Sai Shōki. When she was 15, she saw the Japanese modern dancer Ishii Baku perform in Seoul and was inspired to become a dancer. After convincing her parents to allow it, she traveled to Tokyo and spent three years studying with Baku before returning to Korea, marrying and beginning her career.

Choi’s brother and husband were both sympathetic to socialist politics, and Choi — like European and American early modern dancers such as Mary Wigman and Martha Graham — was attracted by many of the ideals of socialism, particularly the emphasis on feminism and the dignity of the working class. With works like “A Free Person’s Dance” (1931), Choi began to create a Korean sinmuyong, or “new dance” that challenged Japanese Imperialism and traditional notions of femininity.

“There’s a writing where she says, ‘I dance for freedom,’” Jones said. “And I said, oh my gosh — freedom of her country, freedom as a woman, freedom as a Korean.”

Choi’s talent was prodigious, but political and cultural pressures were great. Turning away from socialist realism, she began to add more traditional Korean dance elements to her choreography and by the late 1930s was touring across the globe. When World War II broke out, the Japanese government sent her to entertain Japanese troops, which, once the war ended and Korea was liberated, prompted criticism from Korean nationalists.

In 1946, Choi’s husband, an active supporter of the Workers’ Party of Korea, went to North Korea, and Choi soon followed. She founded a school, toured China, the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries, and began again to create dances with socialist realist themes. But eventually, internal strife within the regime led to a series of purges. Choi’s husband was arrested in 1959 and killed; Choi disappeared in 1967. In 2003, North Korea issued an official statement that she had died in 1969.

Ending up on the wrong side of a geographic and ideological border, Choi became more sullied than celebrated in South Korea and knowledge of her faded.

“It’s such a sad story — a story of war, of assimilation, of erasure,” said Jones.

RIGHTING THE HISTORY

In studios and classrooms in the United States, the known history and techniques of modern dance have been almost exclusively American and European. Research like Jones’s is opening up that tunnel vision.

“What we’re beginning to uncover is that there really were dance modernisms globally,” said Susan Manning, a professor at Northwestern University in Illinois and the author of the forthcoming “Critical Histories of Modern Dance.” “How does this history happen, and we not learn it?”

Photo by YeJin Lee: Dance professor Kim Jones coaching dancer

So Young An for “Dance for Freedom.”

While Manning and other scholars are writing new histories of global modern dance that explore contributions like Choi’s, Jones is bringing that history to the stage in movement that is rooted in the research and resonates with her own dance training, her personal story and the connection she feels to Choi.

“What Kim is doing is very urgent for this moment. She’s not arguing that she’s actually recreating this dance. It’s lost. But how do we reimagine, reperform, reenact, rethink, recover? Kim’s work is making a huge difference in terms of how we understand modern dance.”

– Susan Manning, Bergen Evans Professor in the Humanities, Northwestern University

자유 Dance for Freedom

Photo by Botticelli Foto: Kim Jones and musician Vong Pak perform at a festival in Italy

In late 2019, Jones received a Faculty Research Grant to travel to Korea to meet again with Choi’s former dance student, Kim Yeong-Sun, a North Korean refugee in her late 80s. But the pandemic prevented the spring 2020 trip. Fortunately, So Young An, a current member of the Martha Graham Dance Company, was in Korea at the time. Jones was able to connect her to Kim Yeong-Sun, and with the help of Zoom and production manager Hae Jin Han, could join the two dancers as An learned the historical dance movements.

A year later, Jones, An, and Korean musician Vong Pak came together in person in New York City to begin to create a new work: “자유 Dance for Freedom: Re-imagining the Dances of Choi Seung Hee.”

“When I first heard about this project, it was like my destiny,” said Pak. “Choi Seung Hee inspires me as a diasporic artist. She fought for women in society, for freedom of dance movement. That’s why she is great.”

Jones said that the creative process has “truly been an exercise in collaboration,” with Pak, Han, and An all contributing to the work’s development. Jones and Pak gave a preliminary performance at the Danza Arte Pietra in Italy in June 2022. In January 2023, Pak and An gave the definitive premiere of “Dance for Freedom” at UNC Charlotte’s Faculty Dance Concert.

The 17-minute work, which Jones plans to expand to an evening-length program, opens with a video by Han of Korean pots in the rain. As the rain subsides, the sound of a chime in the wind fades into the meditative tone of the jing, or Korean gong, as Pak, seated at the far side of the stage, begins to play.

Resplendent in a gown of white Korean silk, So Young An emerges slowly from a long gossamer veil, like a bride. Or maybe a ghost become flesh, turning memory into movement and music.

RELATED STORIES:

Kim Jones awarded New York Public Library Fellowship

Meg Whalen is director of communications for the College of Arts + Architecture.