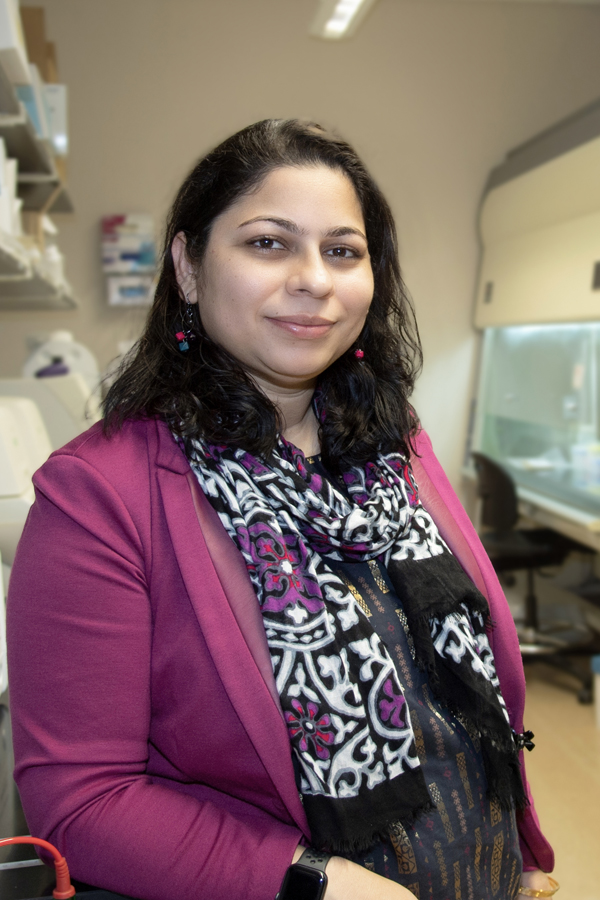

Mariya Munir

Wastewater detective

“Antibiotic resistance has been a silent pandemic; this is a current world problem.”

Mariya Munir, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, is collaborating with Juan Vivero-Escoto, assistant chemistry professor, to explore how light-activated nanoparticles eliminate antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes. Before arriving at UNC Charlotte in 2016, she had been studying antibiotic-resident bacteria and genes long enough to develop a significant expertise – and was eager to delve further.

“My idea was to see how I could come up with different strategies to combat antibiotic resistance in the environment,” Munir said.

“My idea was to see how I could come up with different strategies to combat antibiotic resistance in the environment.”

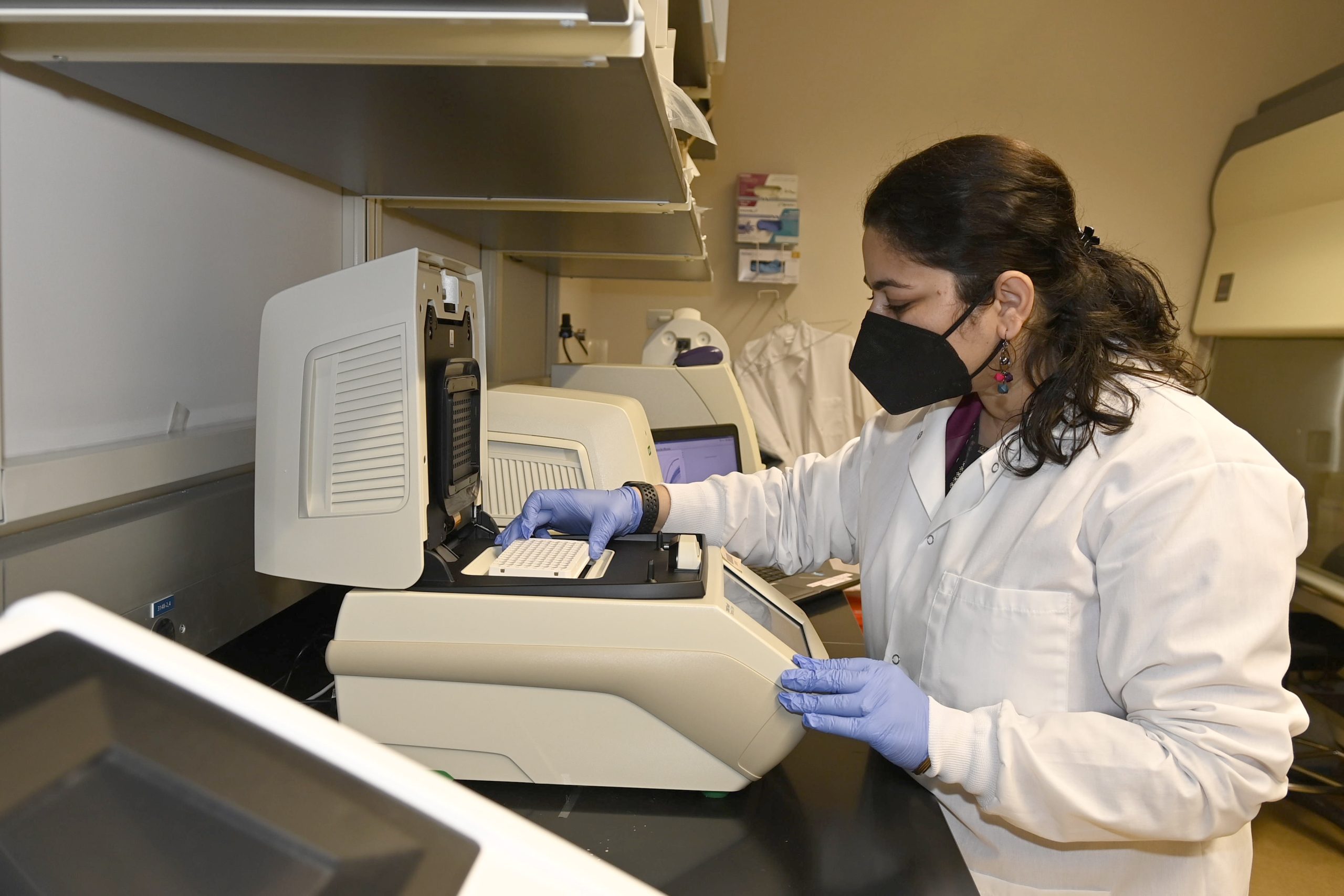

With funding from the National Institutes for Health for their joint research, Vivero-Escoto synthesizes different types of nanoparticles while Munir analyzes and tests those nanoparticles using tools in her specialized lab.

“That’s where the combination of chemistry and microbiology takes place,” she said. The work could have long-term applications for hospitals and other clinical settings as well as for wastewater treatment, since antibiotics get released into the water stream.

The water and sanitation issues Munir saw while growing up in India sparked an interest in water health and its link to public health. She earned an undergraduate degree in biotechnology and a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in environmental engineering from Michigan State University and joined Virginia Tech as a postdoctoral researcher.

Once at Charlotte, she established an environmental microbiology lab at the Energy Production and Infrastructure Center, or EPIC. Her primary research interest is in detection, removal and inactivation of emerging biological contaminants in water and wastewater systems.

Her experience in the application of environmental microbiology techniques to study antibiotic resistance bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants provided a strong foundation for her research on the COVID-19 pandemic. She tracks SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in wastewater treatment plants in Charlotte. She also is involved in UNC Charlotte’s campus wastewater COVID-19 surveillance study, which played a major role in the University’s ability to keep the campus open during the height of the pandemic.

She explains that tracking COVID markers in wastewater serves as an early warning sign that COVID is spreading in the community. “This is a good underlying public health tool that will help monitor not just COVID-19 but any kind of pathogen or contaminant in the environment. It gives public health officials real-time data.”

“Antibiotic resistance has been a silent pandemic; this is a current world problem.”

Mariya Munir, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, is collaborating with Juan Vivero-Escoto, assistant chemistry professor, to explore how light-activated nanoparticles eliminate antibiotic-resistant bacteria and genes. Before arriving at UNC Charlotte in 2016, she had been studying antibiotic-resident bacteria and genes long enough to develop a significant expertise – and was eager to delve further.

“My idea was to see how I could come up with different strategies to combat antibiotic resistance in the environment,” Munir said.

“My idea was to see how I could come up with different strategies to combat antibiotic resistance in the environment.”

With funding from the National Institutes for Health for their joint research, Vivero-Escoto synthesizes different types of nanoparticles while Munir analyzes and tests those nanoparticles using tools in her specialized lab.

“That’s where the combination of chemistry and microbiology takes place,” she said. The work could have long-term applications for hospitals and other clinical settings as well as for wastewater treatment, since antibiotics get released into the water stream.

The water and sanitation issues Munir saw while growing up in India sparked an interest in water health and its link to public health. She earned an undergraduate degree in biotechnology and a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in environmental engineering from Michigan State University and joined Virginia Tech as a postdoctoral researcher.

Once at Charlotte, she established an environmental microbiology lab at the Energy Production and Infrastructure Center, or EPIC. Her primary research interest is in detection, removal and inactivation of emerging biological contaminants in water and wastewater systems.

Her experience in the application of environmental microbiology techniques to study antibiotic resistance bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants provided a strong foundation for her research on the COVID-19 pandemic. She tracks SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, in wastewater treatment plants in Charlotte. She also is involved in UNC Charlotte’s campus wastewater COVID-19 surveillance study, which played a major role in the University’s ability to keep the campus open during the height of the pandemic.

She explains that tracking COVID markers in wastewater serves as an early warning sign that COVID is spreading in the community. “This is a good underlying public health tool that will help monitor not just COVID-19 but any kind of pathogen or contaminant in the environment. It gives public health officials real-time data.”